Like most people, you are probably buying your fish already cut up in pieces for convenience’s sake, but it is actually much more economical and gratifying to buy it whole and prepare it yourself.

I cover here different techniques you can practice to fillet your fish: the Western technique, the Japanese one, and the Chinese one, but also how each of those styles uses a knife for this purpose. You just have to pick and choose what way seems the easiest for you and practice (just make sure to check out the 3 videos I’ved linked to in paragraphs 2, 3 and 4), and you’ll soon won’t buy pre-cut fish fillets anymore!

- How to choose your fish?

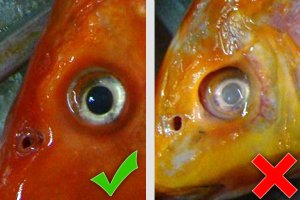

Before you cut it open, you have to buy it. There are a few tips that will help you choose the freshest fishes at your fishmonger’s (from Josh Niland’s great book The Whole Fish)- Make sure the eyes are still dark and not cloudy-ish

- The mucus covering the fish is sign of freshness (even though it might be gross)

- The fish shouldn’t have a fishy smell

- Check the gills and make sure they are red, not brown

- Side note: once you’ve selected your fish, ideally ask your fishmonger to gut it for you. The “grossest” part of the job is then done for you. If you get it still full of guts, the videos below will all show you how to gut your fish, so no worries to have.

- The Western technique

Let’s start with the style that most people are familiar with: Click on this link for the details- The knife: a long and thin filleting knife, the blade is fairly flexible and can really adapt to the fish to remove as much meat from the bone as possible

- The technique: the main difference with the other techniques below is that you work around the head and you never remove it as the knife is too thin and light to separate the head from the body. Another good point is that with this knife, it is fairly easy to remove the skin from the filet.

- The Japanese technique

Obviously, if you think about preparing fish, you have to look at how Japanese chefs do it: Click on this link for the details- The knife: called “deba” (出刃), it is one-bevelled, meaning that it is cutting from one side (so it is important to buy either a right-handed or a left-handed one! Left-handed ones are usually more expensive since there are fewer of those since there are fewer lefties…). A sturdy knife with a wider edge than the Western one, which will have an impact on the technique.

- The technique: as with the Western way, you start by cutting behind the head, but then you chop it off early on thanks to the weight of the night and the thicker edge that allows you to put more force on it to cleanly snap the bone. Once the head is removed, the rest of the technique is similar, cut alongside the back and remove the fillets one after the other

- The Chinese technique

A bit more blunt and brutal, but super efficient, the video speaks for itself when you compare to the 2 other styles… Start at 0:25 and turn on the English subtitles: Click on this link for the details- The knife: the Chinese cleaver, the one and only knife they use (instead of having tons of knives like in French of Japanese cooking, this one knife is used for everything, from the most detailed work to butchering meat).

- The technique: quite efficient and to the point (cut the back of the fish and remove the filets in one fell swoop thanks to the massive blade), but harder to master for whoever isn’t used to this style of knife and you are likely to leave more meat on the bone than anything.

- The finishing touches

As you’ve seen in those videos, once the fillets are cut, you need to remove the belly part and use that special fish tweezers to remove the bones. Have a bowl of water ready and remove the bones one by one and dip the tweezers in the bowl between each bone to easily discard them

- What to do with what’s left of the fish?

That’s where we’re really getting the most value out of our fish as you can use the belly part, the head and the spine with the meat still stuck in between to make any find of fish stock or “dashi” (出汁) that you want.- Add the leftovers of the fish in a pot with water and any vegetables scraps you have ideally saved and frozen, or simply add fresh veggies like onion, carrot, celery and whatever else you want, and maybe some whole spices as well (pepper, coriander seeds, star anise, cloves etc)

- Boil the stock and remove the scum that arises

- Reduce the stock and then strain it before freezing it in an ice cube tray

- Once frozen, put the stock cubes in a ziplock bag. Now you can easily use those stock cubes anytime you need to add flavour to a dish!

As a finishing remark, let me just share my own experience playing around with knives and trying to fillet fish. Even though I have the Chinese knife, I haven’t yet tried this method, but I have tried filleting sea breams with both the Western filleting knife and the Japanese deba knife, just so that I can compare all things being equal.

My personal preference goes the deba as you can easily snap the head off and it makes it easier to then open up the back and belly of the fish once the head is removed, compared to the Western knife where you have to keep it and try to break the bones around the head when you are trying to detach your fillets (check the first video around 8:48 to see what I’m talking about).

Try it out for yourself, and don’t forget to call your Otosan and ask him to come down to the kitchen and watch you fillet fish like a pro. Eyyy!